Viggo Wallensköld began his artistic training at the University of Helsinki’s Piirrustusluokka art class. In 2005, he was named Finland’s Young Artist of the Year. To date, he has held eight exhibitions at the Bäcksbacka Konstsalong gallery. His latest solo show in Helsinki was at Galleria Halmetoja in 2020. He has also exhibited widely in other venues both in Finland and further afield, and his works are featured in leading Finnish art collections. Viggo Wallensköld has published four fiction titles, with the latest two released under the Kustannusosakeyhtiö Siltala imprint.

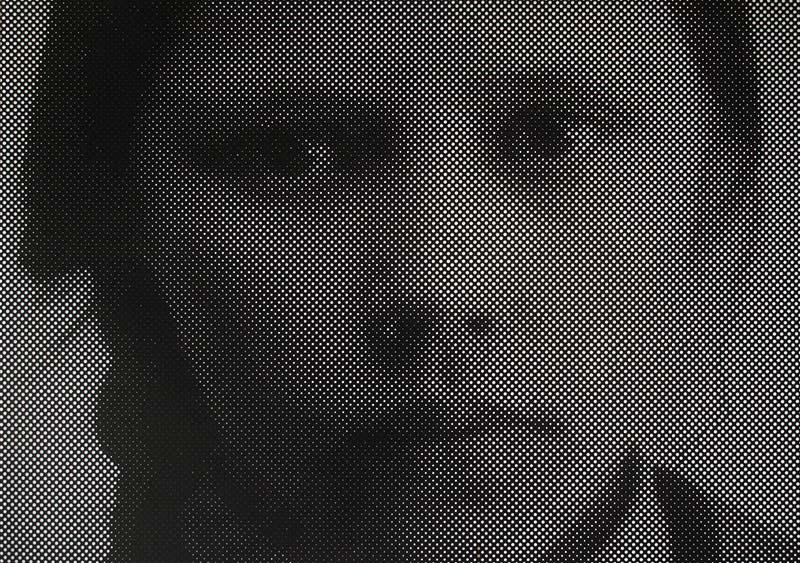

Painter and author Viggo-Wentzel Renato-Bogislaus Cathmor-Adlerwalt Wallensköld, aka Viggo Wallensköld, depicts life’s absurdity through a series of fictional characters. Over the years, his works, which typically feature just one main character, have come together to form a cohesive entity, a universe all of their own, comprising a series of intertwining themes.

Wallensköld’s paintings explore the physical diversity of humans and our ability to cope with difference. He himself has said that his paintings emerge from a sense of shame, his own experience of otherness. From the early 2000s onwards, he has explored body positivity and non-binary identities. His treatment of these topics is characterised by its restraint and emotional deftness. The people depicted in his paintings do not represent a stereotypical physicality but nevertheless expect to be seen. Visibility matters.

As the artist himself has acknowledged, there is always a touch of the autobiographical in his paintings featuring people, but they are by no means self-portraits, or even portraits for that matter. Often, his imaginary subjects have borrowed poses, outfits and even facial expressions from the artist’s old family photographs, from people Wallensköld himself has never met.

The main character featuring across his literary works is a mycologist that bears more than a passing resemblance to Wallensköld’s father, who himself is an artist with a passion for fungi. The Rabelais-esque atmosphere of Wallensköld’s experimental novels is complemented with illustrations created by the artist himself. Rendered in watercolour and ink using his sublime and highly distinctive technique, his book illustrations have been compiled into series and included in various museum collections.

In technical terms, Wallensköld’s creative process is one of functionality – the approach is determined by the desired outcome and atmosphere. Wallensköld’s brushwork technique ranges from light, single layers of colour to repeated applications of pigment that results in an even finish. The temperature and temperament of his works range from highly expressive to calm tranquillity.

A key theme among Wallensköld’s paintings of people is the link between the organic and the inorganic, between man and machine. His perhaps best-known work on this theme is the machine-human, where a person’s head or another part of their body is connected to a machine that maintains its functions. The machine can be switched on and off, it can be set in hibernation mode or placed on a windowsill, like an ornament. And yet it is partially comprised of an intelligent, sentient person, to whose thoughts we are granted no access. Wallensköld offers us a wonderfully straightforward take on the highly topical and relevant issues of AI, robots and humanity. He deconstructs this angst-inducing topic with considerable skill, rendering it accessible and relatable.

The links between the animate and the inanimate are also the theme running through Wallensköld’s cemetery-themed works, where gravestones and memorials are used to construct portraits of the dead. As with historic photographs, Wallensköld has the ability to bring headstones and plaques to life. Stories build up around them, making their subjects feel real.

When real people are featured in Wallensköld’s portraiture, he often pairs them with an attribute. These symbols are chosen for their ability to open those depicted up to our interpretation. Rather than reaching for birds, cloaks or arrows as commonly seen in religious art, Wallensköld uses a range of everyday, instantly familiar items: bookshelves, furniture, toys. From time to time, a single item is not enough, and he creates an entire interior around his subject, evoking a time and a place that doesn’t exist but can be effortlessly imagined.